Hello! My name is Marrije Schaake. I work at Eend. Sometimes, my role is project manager. Sometimes my role is information architect. But I’m always the business manager of our company: the one who ensures that we have enough work, and work of the right quality. And, of course, I have to make sure that we make a profit.

I have been doing this work for quite a while: I’ve been with Eend since 1999, so fifteen years now. In that time, we have done a lot of projects, and a lot of Phase Two projects, too: extensions to earlier projects, and extensions to extensions, and also new projects for the same clients - which is a Phase Two in itself.

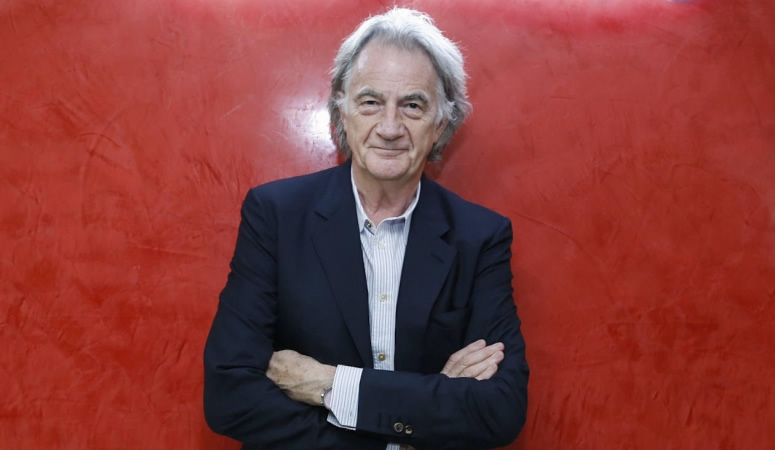

Today, I’m here to talk to you about How to deal with Phase Two, but I’m mostly going to talk about this guy.

This is Paul Smith. I want to be Paul Smith when I grow up. He’s awesome.

So who is Paul Smith? He’s a British fashion designer - he started off very humbly, in 1970, with a single, tiny shop in the glamorous city of Nottingham. He didn’t have any education, didn’t know anything about fashion really, but he showed grit and determination and business savvy, and he built an empire from those humble beginnings.

He now does 28 collections a year, has over 200 shops in Japan alone, and his clothes are sold in 66 countries. In the year 2000, he was even knighted by the British Queen, so he’s Sir Paul Smith, much to his own amusement.

There’s a show on at the Design Museum in London about his work at the moment, called ‘Hello, my name is Paul Smith’. Which I haven’t seen alas, and probably will not see at all, since it’s only there until June 22nd.

Fascinating, I hear you think. This guy is a successful fashion designer. Good for him. But how is that relevant to my work? Or to HER work?

Let me tell you about that. Paul Smith isn’t just a successful guy: he’s also THE most relaxed guy I have ever seen.

You’d think running such a large company would be a very stressful thing: all those people depending on you, all those collections to be designed, shops that need to be designed and run, production lines, taxes, international currencies, grueling travel schedules, jet lag, talking to Japanese people… Just thinking about the complexities of his day makes my head hurt.

Nice guy

And yet he is really, really relaxed. All the time. Also, he has fun. He really enjoys his work. He’s nice to people - to journalists, to clients, to his employees. He’s not some frothing Gordon Ramsay of fashion - this is a genuinely nice guy.

How the hell does he do that? I want to be able to do that! And I bet YOU’d like to be able to do that as well.

Who wouldn’t want to be relaxed and happy at work, flowing effortlessly and productively with all the stuff the days and the weeks throw at you?

Also, with all those collections and all those shops, Paul Smith’s life is basically one big long Phase Two: he keeps having to build on the stuff he has done earlier, for people he has worked with earlier. So he has to deal with legacy and with staying fresh - and he has to stay solvent.

What is his secret? And can I steal it?

Relaxed and happy

I don’t think there is one particular secret thing Paul Smith does that makes him this relaxed and happy - rather it’s a couple of things. And I think we can all use them to make our working lives a bit easier.

And particularly the bits of the working life that lead to stress - such as some of the following things you might run into:

how to get a clear picture of what is and isn’t part of that delightful phase two in projects,

the irritatingly vague aspects of what belongs in the “maintenance phase”,

impatient clients calling you with knotty problems when you are on holiday,

or clients who don’t listen to your expert advice.

So. What can we learn from Paul Smith? That will make us relaxed and happy and hugely successful? I’ve been thinking about that, and I’m going to talk to you about four things you can apply in your own work, plus a bonus thing at the end, that’s more of an experiment we might embark on together.

And we’re going to start off with the one that I think is the most important one for all of us, from a business perspective.

1. Assumptions

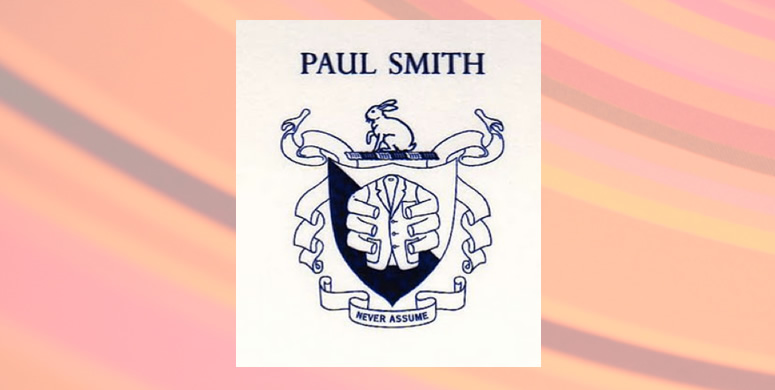

This is Paul Smith’s coat of arms. It’s now fourteen years old - he got it when he was knighted in 2000. But when he shows this picture to an audience, he still dissolves in really charming giggles: look, it’s a coat of arms! Get it? Get it? There’s also a lucky rabbit in there, very nice.

But the legend below is the serious part, and it’s a very useful message: “Never assume”. I don’t know about you, but this is something that keeps tripping me up, even after all these years of running a business.

Do not assume you have the same view of the project you are working on as the client. Actively figure out what your assumptions are and make things explicit.

I may be assuming that the client will paste their new content into this extension to the website we’re doing together - but maybe they think they will just send me a big stack of Word documents and that I will throw that content in at the last moment.

I may be assuming that the client knows I will not do updates for free after this phase of the project is finished - but the client may have a mental model in which essential updates are just that: essential, and therefore part of the package.

I may be assuming that the client will want to track their visitor numbers with Google Analytics - but maybe they have just decided on a new policy that states they hate Google and they don’t want all those cookies on their site. Which means we will need to do something else entirely. This is one that happened to us when were designing a website for a political party that had a very strict policy about cookies. The Analytics thing was actually rather easy to solve, but try to do something with webfont licences that doesn’t involves cookies, and you’re in a lot of trouble.

All your assumptions may be entirely reasonable and even realistic, but they are still assumptions, and you should check them.

By the way, asking your clients about these things doesn’t have to be confrontational at all. And you don’t have to become a micro-managing weirdo drowning in checklists - but it DOES pay to regularly check your ongoing projects mentally and ask yourself “what am I assuming here?”

In fact, it might be a good exercise to regularly sit down, close all your tabs, put the phone on silent, and quietly think about each of your projects or clients. Just list for yourself what you may be assuming in this project, or in this new addition you’re doing. Write it all down.

And then of course you will CHECK all of those assumptions. Most of these things can be checked with a quick phone call or in one of your regular meetings with your client.

And you will also agree with your client on whether you will have to make a formal note of things. Will you put things down in writing? Or is a verbal agreement enough?

If you’ve done this for a while and have gotten into the habit of thinking about all your assumptions regularly, you can have a notebook or a stack of post its nearby to note down any small worries that spring up when in the course of your day. But you have to get into the HABIT of consciously naming the assumptions first - and growing that habit takes effort and concentration - so start with dedicated time for this activity.

If you have a good client, there will also be someone on the other side doing this sort of checking. But just because there is a project manager involved, you should never assume (see?) that he or she will take care of everything.

By the way, I’m not saying this is EASY. It’s actually pretty hard, especially at first. Both uncovering your own assumptions and acting on them. In fact, when I was preparing this talk, my colleagues and I talked about this “Never Assume” business. And then a project came up in which I should really check something with our client. But it’s a painful thing, that I don’t want to do. Also a client I really don’t want to call, because she’s a bit woolly and vague and we tend to get into arguments over the phone. Which is annoying and draining. So, nggggg. And because of this talk I now have two colleagues who keep chanting “never assume! never assume!” at me…

.jpg)

So: If you want to be happy and relaxed and Paul Smithy: never assume, take time to think about your assumptions and talk to your client about anything that could trip both of you up later on. If there’s only one thing you remember from this talk I want it to be this - so remember Paul Smith’s coat of arms and Never Assume.

2. Money

Thinking about what our work should cost is a source of a lot of anxiety for me, and maybe for you, too. Particularly in this economy, we’re often up against competition who will do the work for less money than we do. And we need work, too. So there’s always this temptation to think about lowering your price.

This may, oddly enough, especially be the case when you’re doing follow-up projects for existing clients. We’ve already done the Big Project - now we just need to add a couple of little things, surely that can’t be too much work, can it?

Your client may think like that, and you might even think like that a little bit yourself.

Don’t do that, please. If you are a professional, you should be paid professional amounts. Fees that leave you enough room to do a little extra, have a little padding. You need this padding - not so much to buy Ferraris, but to have the space in your life that will allow you to continue to improve your skills.

Paul Smith clothes aren’t cheap. They are a lot more expensive than clothes from Zara or H&M. But they last a lot longer than stuff from the high street as well - there are some Smith items in my wardrobe that I have had and worn for years and years, and they are still in very good condition. They are also still fun and pretty to wear.

This is because the company has made a commitment to make interesting, high-quality items that will last a long time. Which makes them, yes, more expensive. But the higher price gives the company the budgeting room to select higher quality cloth, to buy fun and interesting buttons to use, to have the extra time in the budget to make that interesting and fun contrasting stitch instead of a boring old stitch that would have been so much faster.

“I don’t worry about profits or losses. I prefer to be free and relaxed, to enjoy every day of work.”

But that doesn’t mean he is some kind of hippy-dippy dreamer, because the quote goes on:

“I know the production cost for every t-shirt, I know the profit the company will make from its sale, but I never think that we could have earned fifty more pounds.”

So it’s a balance. You can (and probably should) be aware of what your pricing structure is, and get the basics totally right. But over and above that, there should be a cushion in each project, even in the extension projects, the Phase Two stuff.

There should always be room to pay attention to details, to make those delightful little things that make a project really cool or good, the nifty things that make you happy because you made them.

Make that room for yourself. It’s important. Also in Phase Two - don’t fall into the trap of the race to the bottom, in which you more and more turn into that famous “pair of hands” that will just do the tactical work.

A good professional deserves to be paid well for his or her work - well enough to allow for the little professional touches that make it all worth it. And after that cushion has been taken care of: let it go - no need to go for those extra fifty pounds the company could earn.

3. Right vs easy

“Remember to do things that are right rather than things that are easy”

Let me explain that.

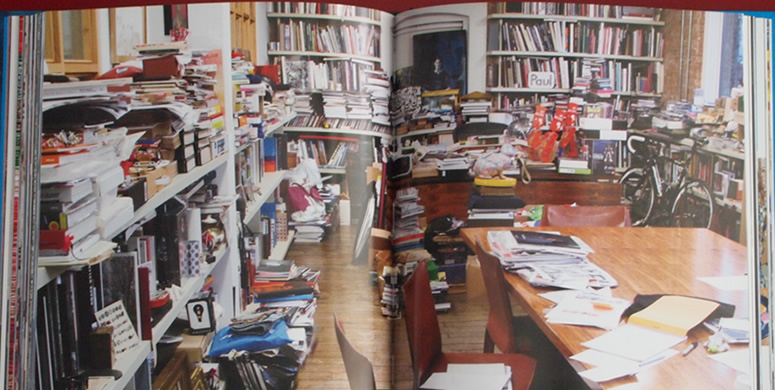

This is Paul Smith’s office. It’s a huge mess. It’s filled to the brim with books, trinkets, drawings, things he gets in the mail from admirers, stuff.

And in this messy room, nobody is allowed to touch anything, because it all has to stay in the exact same place, or Smith won’t be able to find the thing he is looking for. He knows exactly where everything is. Amazing.

Does that look like a serious office to you? Does that look like the room in which all those decisions affecting the entire sartorial empire are made? It doesn’t to me. But it works.

There’s a wonderful documentary made by a couple of French people, called ‘Paul Smith, Gentleman Designer’. I highly recommend it - you can probably get it on Amazon and Dutch people can certainly see it through Uitzending Gemist.

So: messy room, messy filing system.

That’s another thing I admire hugely about Smith: he’s not afraid to be himself. If he finds a thing that works for him, he’s not afraid to stick to it, even if it’s not exactly conventional. Just because everybody does a thing a certain way, it doesn’t mean that it’s a law of nature that things should be done that way.

You can always think about what’s right for you - what makes YOU happy. And you can do exactly that thing. But you’ll have to do the hard work of being honest about what really floats your boat, or doesn’t. Which mostly means being honest with yourself. And then honestly communicating about it, so people will not have to guess about your intentions or rules. Which may be scary. But worth it.

Take Service Level Agreements for instance. They sound like a good idea: a number of clients who pay you a regular fee each month to have that warm fuzzy feeling that you will solve any problems they have within a certain number of hours. In most months nothing much happens, so it doesn’t take much of your time really. Also, it’s a professional thing to do, a Service Level Agreement. All the huge IT companies offer them, they are serious, grown-up things to offer. Really, you can’t do business without them.

But maybe you really hate them. Maybe you find that the obligation of always having to be at the beck and call of these people severely cramps your style. Just the thought that you might have to interrupt what you’re doing at a moment’s notice, even if you are ill or on holiday or in the middle of a fascinating new project - that might give you such a case of the hives that the steady income from an SLA is totally not worth it.

I think it’s a valid option to NOT offer service level agreements to your clients. If you really don’t want to do them - don’t. There are lots of other options. You can train someone at the client’s to do their own maintenance. Or you can hand over the maintenance to a fellow developer who does like this type of work. Or you could just have a conversation with your client about this and say ‘look - I’ve paid extra special attention to robustness in this project, and there’s really not a lot that can go wrong in the short, hair-on-fire term. You don’t need to pay me to be on call. You CAN call me, and I’ll help you as soon as I can, but there are other things going on in my life as well, so it might be a while.’

In this way, you stay true to yourself and to the way YOU want to work. If being under an SLA makes you feel like a slave, and you don’t want to be a slave, don’t be one. That will just give you stress, and we want to be happy and relaxed and enjoying work.

My friend Arno does this, for instance. He gives absolute priority to his family - his children and his wife are the most important thing in his life. He’ll basically help you with anything, but not if it’s time to take his kid to ballet class or scouting - it will just have to wait for a little while. And if he’s on holiday, he’s on holiday - he’ll help you if he can, but on his own terms. Arno is a really relaxed guy as well - and I think it’s because he has his priorities straight and isn’t afraid to stick to them. Which I admire hugely.

Of course, this may not work with all clients. There may be clients who are absolutely convinced that they cannot live with a developer who is a one-person shop, or doesn’t offer 24/7 support, or isn’t prepared to draw up a hundred-page SLA. And that’s alright. Then maybe you aren’t a good fit for each other.

Your life is just as much determined by the ones you walk away from as by the ones you engage with. You can’t please everybody all the time. And that is fine: your primary responsibility is your own happy relaxedness - if you find something in your work life that isn’t working, that’s not fitting who you are - find ways to get rid of it and turn it around.

Paul Smith clothes aren’t for everybody. That’s fine. The way he arranges his office may not be traditional and may earn him some laughs from serious business people who are convinced they know what they are doing. That’s fine too. Let them laugh. It works for him, and he’s the most relaxed guy I know, so there.

4. Start something new every day

One of the biggest challenges when you work in a field for a long time is staying fresh. Staying up to date, and interested, and creative. Paul Smith has this challenge all the time: if you have to design 28 collections per year, you have to keep looking for inspiration, basically non-stop.

In the documentary I mentioned earlier, we see how he does this. We see him cycling through Paris very early in the morning, looking for nice little details to photograph. He’s at a deserted fun fair, where he takes pictures of all the riotous lights and colours - keeping up a running commentary about how this is all inspiration for scarves and wallets and other accessories.

He also makes these little rules for himself, to keep things interesting. One of the rules is that no two of his shops are ever the same: each of them has a unique design and interior. The shop in Paris has a whole room that has been wallpapered with real pennies, for instance. The Los Angeles shop is a very interesting and very pink concrete box. And at the show at the Design Museum there is a whole wall of coloured buttons.

One of Smith’s trademark ‘sentences’ is “start something new every day”. I think this really helps him to stay interested and aware and playful. But I also find it a bit troubling… If you start something new every day, what about FINISHING? I’ve already got so many projects lying around that were never finished - I don’t know about you, but you may recognise that situation. Should I really start something new again and again and again? Will that not just increase the guilt?

(Here I referred to Joel Bradbury’s talk half an hour earlier. Joel encouraged us to ship ship ship, to do the hard work of finishing stuff and putting it out in the world, early and often.)

Finishing stuff results in momentum, but consistently STARTING stuff brings a lot of momentum, too. If I’m just obsessing about all the things that haven’t gotten finished yet, and consequently don’t start new stuff any more, it’s a net loss. It’s all about energy - getting that great flywheel of energy started and in rotation. So on balance, I think that yes, “Start something new every day” is still very good advice.

5. So now for the bonus tip: Don’t read

Paul Smith is severely dyslexic. This hindered him a lot a school - he left school at 15, and missed out completely on any formal education - both an education in a fashion college and education in how to run a business.

I admire his ability to just get up on a stage and do a very interesting presentation without any notes - we saw him do that at the What Design Can Do conference a few weeks ago, and it was wonderful. But he’s got no choice: he wouldn’t be able to read his notes quickly enough to be able to do the presentation, because of the dyslexia.

So really he has no choice. But he also turns this handicap into something that sets him apart from others - if you don’t read, you don’t get weighed down so much by all that information coming at you from all corners of the world.

Oh come on, you’ll say. I can’t stop reading! I NEED to read - how else will I keep up to date with everything that is going on in my field? And in my clients’ fields! I can’t be a good developer or designer if I don’t keep up with the blogs and Twitter and the news - I’ll be a laughing stock in no time.

This may be true. It may also be not-true.

There’s almost nothing I love so much as reading. Anything and everything, basically. But I can’t deny it’s often a form of procrastinating, something I do to get away from stuff. I admit I fall into the trap of reading just one more article, just one more news story to get away from doing the hard productive work that needs to be done.

And it’s not just professional literature, you know, stuff that actually helps me do my job, like article about usability or SEO or my great love the Internet of Things.

It’s also the news, and gossip, and deep thinky pieces about Edward Snowden and how the world is going to hell in a hand basket. All these things I can be upset about, and have an opinion on, have strong feels about - strong feels that take me away from doing the things that actually make a difference.

Also they, you know, upset me. And in most cases there’s not one thing I can do about them. I can worry all I like about refugees in Syria, but they really aren’t in my circle of influence: I can’t help these people by worrying about them and reading more and more about the situation in Syria. Or, you know, Miley Cyrus’ hair.

So, perhaps, it’s not such a bad idea to clear up some space in my head and in my day and just not read. It may lead to a lot more relaxation and happiness.

This is what Paul Smith himself says about that:

“I don’t want my mind to be polluted by data that doesn’t interest me.”

It goes on:

“If you can achieve a certain detachment, you can enjoy a life free of worries, of comparisons, of thinking that so and so is more famous or has more money than you do. It’s a philosophy for living.”

So people will poke fun at you. Big deal! Think of all the time you will have to actually make stuff! To be interested in things, to tinker with them. All those opinions will get you nowhere, just in a place of insecurity and comparing.

I am, of course, talking to myself here… But go ahead, give it a try for a while. It might be very freeing.

So - in conclusion - keep in mind that you should pay attention to making enough money, doing the hard work of staying true to yourself, and remember to start something new every day. Let’s experiment with not reading. And also: Never Assume.

And let’s all be happy and relaxed. Thanks for your time!

(Transcript of my talk at GeeUp in Leiden, on June 20th 2014.)